Dear Reader,

Hello from 2025, Happy Imbolc & A Happy Lunar New Year!

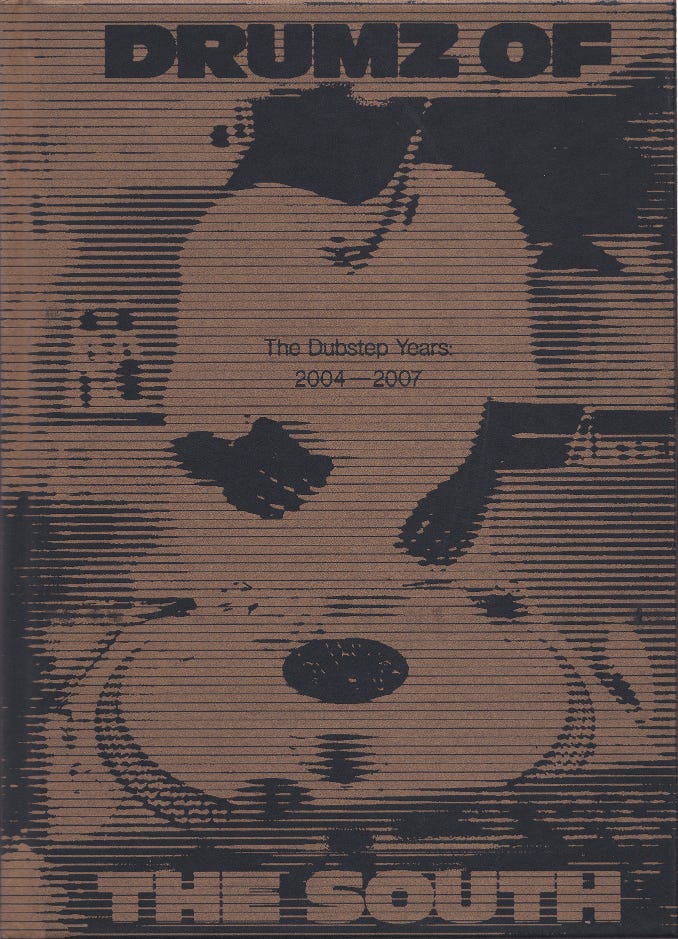

Since my last newsletter, I have published a book! The second edition of Drumz Of The South: The Dubstep Years was released last Autumn on the excellent Velocity Press, a UK imprint dedicated to publishing books and pamphlets about music and culture. This updated edition features a fresh design by Alfie Allen and newly commissioned texts by Charlie Dark MBE, Martin Clark aka Blackdown and Jason Goz, plus myself, Emma Warren and DJ Flight in conversation. It is available here and in all good record and book stores.

This year, I’m expanding this newsletter to include fragments about my other favourite medium, music! This will give me the chance to share some of what I’m learning as I research for an exciting new project that I’ll reveal in good time. It also gives me an extra space to share photographs from my music related archive. Plus I’ve finally added a paid subscription option which will offer exclusive peeks into unseen or rarely seen parts of my archive, discounts on prints and books and for Of Gold members, a 1:1 mentoring session.

One thing that’s been swirling around my head for the past couple of weeks is the DIY production spirit of early dubstep and grime. It’s fairly common knowledge that these genres were, for the most part, built in home studios by teenagers and young people making sonic magic with whatever equipment they could get their hands on. Personally, while I was privy to a few home studios of the time, photographing Digital Mystikz and Loefah in theirs for example, my knowledge of the actual equipment and software used is fairly basic.

I’ve always known that Fruity Loops (now FL Studio) was a major player in dubstep’s distinctive sound; that other programmes like Reason, Logic and Ableton were utilised and that Burial’s adoption of Sound Forge to create his signature sound was very unconventional. But until last week, my knowledge pretty much ended there.

Then I remembered the long-standing rumour that a lot of early dubstep tunes, especially from Skream and Benga, were made using Music 2000, a game for the PlayStation 1. I spotted a Reddit thread suggesting that The Judgement (by Skream & Benga) was one of them, so I asked for confirmation via Insta stories, tagging Benga, who swiftly told me that it in fact, it wasn't.

In this absolute gem of a BBC recording, you can hear Benga making an 8-bar beat using PS1:

My next enquiry was Pulse X by Youngstar (often credited as the first-ever grime beat) and another tune posited on the web as being built with a PS1.

Wrong, as my friend, the writer Dan Hancox, who once believed this himself, let me know.

Dizzee Rascal’s Boy in Da Corner was then put forward. DJ Martelo thought so at first, but then immediately found a Vice article that debunked the theory.

Just as I was about to conclude that PlayStation 1-made dubstep and grime beats was actually a 32-bit myth, Dan came through with a revelation from his book Inner City Pressure: Dizzee’s Stand Up Tall (Showtime LP), half of So Solid Crew’s (incredible imo!) first album, and several JME beats were in fact made on a PS1. JME has both rapped and tweeted about using other consoles and games like Nintendo’s Mario Paint game as creative tools; pure ingenuity

.

Dan also reminded me that Ruff Sqwad made some of their legendary beats on PCs their parents gifted them for homework, which took me straight back to my own DIY days. In 2003-4, I’d stay late at the newspaper where I worked, using the office computers and photocopiers to create zines and newsletters, which eventually led to Drumz of the South.

And it’s not just a UK thing. Rinse FM’s Elle Clark, while making her recent show The Raptor House Story, found out that Venezuelan producers were also using game consoles to make beats. That DIY, make-music-by-any-means energy? It was global.

While there remains a question mark over which, if any dubstep tunes were made on a PS1 (let me know if you know off any!), I’ve very much enjoyed this worm-hole. It has reminded me that creativity thrives when we use what’s easily available to us. Some of the most influential tracks from what Simon Reynolds calls the Hardcore Continuum (e.g the family of Jungle and Garage related music) weren’t made in high-end studios but on PlayStations, early PCs and bedroom setups. It’s evident that it’s not tools that make an artist, but vision, resourcefulness and playfulness.

Until next time,

Georgie

If you enjoyed this letter, please feel free to share it with friends.